What About Someone Who Uses Emergency Services Twice A Month

- Inquiry article

- Open Access

- Published:

Who uses emergency departments inappropriately and when - a national cross-exclusive study using a monitoring data system

BMC Medicine volume eleven, Commodity number:258 (2013) Cite this commodity

Abstract

Groundwork

Increasing pressures on emergency departments (ED) are straining services and creating inefficiencies in service delivery worldwide. A potentially avoidable pressure is inappropriate attendances (IA); typically low urgency, cocky-referred patients improve managed by other services. This written report examines demographics and temporal trends associated with IA to assistance inform measures to address them.

Methods

Using a national ED dataset, a cantankerous-sectional examination of ED attendances in England from April 2011 to March 2012 (n = 15,056,095) was conducted. IA were defined as patients who were cocky-referred; were non attending a follow-up; received no investigation and either no treatment or 'guidance/advice only'; and were discharged with either no follow-upward or follow-up with primary care. Small-scale, nationally representative areas were used to assign each attendance to a residential measure of deprivation. Multivariate analysis was used to predict relationships between IA, demographics (age, gender, deprivation) and temporal factors (day, month, 60 minutes, depository financial institution holiday, Christmas catamenia).

Results

Overall, 11.7% of attendances were categorized as inappropriate. IA peaked in early childhood (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 1.53 for both ane and ii year olds), and was elevated throughout late-teens and immature machismo, with odds reducing steadily from age 27 (reference category, age twoscore). Both IA and appropriate attendances (AA) were most frequent in the nigh deprived populations. However, relative to AA, those living in the to the lowest degree deprived areas had the highest odds of IA (AOR = 0.89 in nigh deprived quintile). Odds of IA were also higher for males (AOR = 0.95 in females). Both AA and IA were highest on Mondays, whilst weekends, bank holidays and the catamenia between 8 am and 4 pm saw more IA relative to AA.

Conclusions

Prevention of IA would be best targeted at parents of immature children and at older youths/young adults, and during weekends and bank holidays. Service provision focusing on access to principal care and EDs serving the most deprived communities would take the about benefit. Improvements in coverage and data quality of the national ED dataset, and the addition of an appropriateness field, would make this dataset an effective monitoring tool to evaluate interventions addressing this issue.

Background

Emergency departments (EDs) are an integral service for healthcare systems worldwide, providing immediate betoken-of-access treat urgent medical atmospheric condition and injuries. Despite this, across the globe, pressures and crowding are resulting in increasingly strained and inefficient ED services, leading to increased waiting times and treatment delays, impaired access, financial losses for providers, and upstanding consequences [1, 2]. A potentially avoidable part of increased pressures on ED services is 'inappropriate' attendances (IA); patients who self-refer with depression urgency problems that are unlikely to crave admission and are more suitable for other services, such equally primary care, phone advice helplines or pharmacy [iii]. Wide variability exists when estimating the prevalence of these attendances, due in role to varying definitions and the subjective nature of measuring inappropriateness [four]. Notwithstanding, internationally, between 24% and twoscore% of all ED attendances are thought to be inappropriate [4]. Such IA can hinder the ability of EDs to treat attendees in a timely and consequently safe manner. Whilst low complexity patients may accept a minimal result on waiting times for more urgent attenders [5], non-urgent cases may as prohibit admission for real emergency cases [six] and have a negative impact on staff attitudes [7].

In England, IA to EDs are a long-continuing problem [8]. Despite previous attempts to reduce their occurrence (for case, through advising people not to use EDs for non-urgent atmospheric condition and by providing a principal care service in EDs [9–11]), IA are thought to remain a brunt on ED services. One local report of patients from two health centers attention a single ED found that 16.viii% of attendances were inappropriate [12], while a broader report of ED use in one London borough reported that 78% of all attendances were potentially avoidable [13]. Beyond England, increasing omnipresence figures and bereft staffing levels are placing the ED organization at crunch indicate, with hospital trusts increasingly failing to meet four-hour waiting time targets [14–xvi]. With an urgent demand to reduce electric current burdens on ED services, developing and targeting interventions to reduce or manage levels of IA should exist a priority. Every bit a first pace to achieving this, it is necessary to proceeds a good understanding of the burden IA place on EDs, the types of people most likely to present inappropriately, and when such attendances are most likely to occur.

When previous studies of inappropriate or avoidable ED attendances in England have been conducted [12, 13], they take focused on unmarried or multiple hospitals in local areas. This study explores IA across England as a whole. Since 2007, records of attendance to National Health Service EDs in England have been recorded into an experimental dataset using the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) arrangement. This written report utilizes these information to make up one's mind the electric current prevalence of IA in England and details the demographic and temporal profiles of these attendances.

Methods

We extracted data from the HES A&Eastward arrangement, for all attendances to ED betwixt 1 Apr 2011 to 31 March 2012 (northward = 17,470,479). The HES A&E organisation includes major EDs (that is, consultant led, permanently open up and with full resuscitation facilities), specialty EDs, walk-in centers and minor injury units. The 2011 to 2012 dataset is estimated to include 80.v% of all English language ED attendances [17]. Extracted variables included: attendee age, gender and area of residence; date and time of inflow; attendance disposal; attendance category; section type; primary investigation; and primary treatment. We excluded attendances to National Health Service walk-in center departments (north = 912,167); those with missing or unknown gender (n = 191,262); those with unknown historic period, missing age or an age likely to be unreliable through extreme onetime age (≥110 years; due north = nine,901); those with missing area of residence (n = 171,427); those with attendance category non known (north = 2,727); those with patient group brought in dead (n = 1,969); and those with attendance disposal category 'left earlier existence treated', 'left having refused treatment', or missing (n = 650,848). The remaining sample was xv,530,178.

Attendances were mapped to area of residence by lower super output area in the HES data. Lower super output areas are a standard geography of mean population 1,500, and each is assigned a ranking of impecuniousness by the Index of Multiple Impecuniousness, a drove of indicators across seven domains of deprivation. Thus, each omnipresence was assigned to a national ecological mensurate of deprivation based on their lower super output area of residence [eighteen].

Attendances were assigned to two groups of appropriateness: appropriate attendances (AA) and IA. Attendances were assigned to AA if the source of referral was any other than self-referred; attendance category was planned follow-up; the attendance had a valid investigation code other than 'none', or a valid handling code other than 'none' or 'guidance/advice only'; and disposal method was either admission, referral to dispensary, transfer to other healthcare provider, referral to other healthcare professional or other. Attendances were assigned to IA if the source of referral was self-referred; omnipresence category was the initial ED omnipresence or unplanned follow-up; investigation code was 'none' and treatment lawmaking was either 'none' or 'guidance/advice simply'; and disposal method was discharge with no follow-upward or discharge with follow-up from general practitioner. Attendances that did not friction match these criteria were excluded (3.1% of remaining sample). The final sample size was fifteen,056,095.

Data were analyzed in Predictive Analytics Software (PASW®) v19 (International Business Machines Corporation, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Armonk, New York, Usa). Initial analysis of demography and time variables was performed using chi-squared on the two groups of ceremoniousness. Generalized linear modeling was used to calculate estimated marginal means for weekday and calendar month. Estimated marginal means are used when average values require correcting for the impact of other misreckoning variables. Astern conditional binary logistic regression was used to calculate adapted odds for IA compared with AA by demographic variables and time variables separately.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Liverpool John Moores University Research Ethics Committee.

Results

Of the 15,056,095 attendances included in the analysis (86.2% of all recorded attendances), 88.3% (13,294,819) were categorized every bit AA and 11.vii% (1,761,276) as IA. Rates of IA per 100 attendances were highest in those under 16 years of age and everyman in those over 85 (xv.04 and 2.43 per 100 attendances respectively; P<0.001; Table 1), and were college in males than females (12.26 and 11.12 per 100 attendances respectively; P<0.001; Table one). Every bit deprivation increased, the total number of both AA and IA also increased. For IA, this increase was from 256,624 in the least deprived quintile to 474,652 in the virtually deprived quintile. Withal, no distinct relationship existed when considering IA rates per 100 attendances, with the second most deprived quintile having the highest rate and the fourth near deprived the lowest (12.03 and 11.50 respectively; P<0.001; Tabular array 1). The highest proportion of attendances in both IA and AA groups was made up of individuals who only attended the ED once in the fourth dimension period (46.6% in AA; 53.9% in IA). The charge per unit of IA was highest in single attendances and lowest in individuals who attended eleven to 20 times (13.28 and seven.41 respectively; P<0.001; Table one).

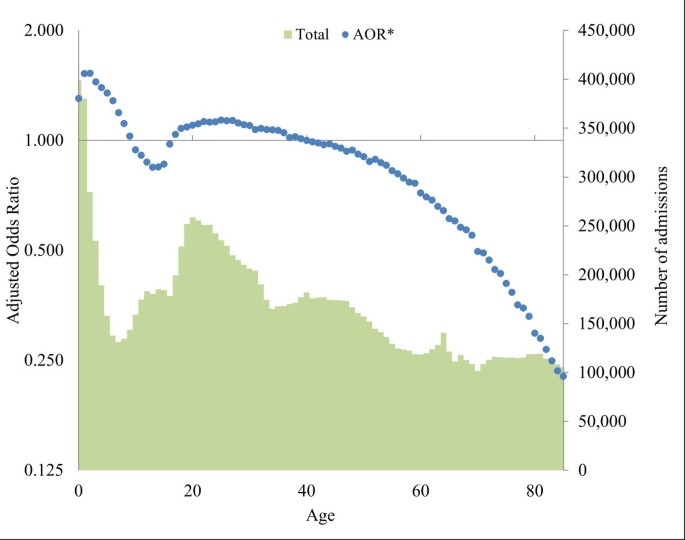

In multivariate analysis, relationships between IA and both age and gender remained similar, whereas the human relationship with deprivation reversed compared with total attendances. Females were less likely to attend inappropriately than males (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 0.95; P<0.001), whilst odds of IA decreased with increasing deprivation, with residents from the almost deprived quintile having the lowest odds of IA (AOR = 0.89; P<0.001; Table 2). Age showed a strong human relationship with IA (Effigy 1). Adjusted odds peaked at ages one and two years (both AOR = ane.53; P<0.001), and then fell through to historic period thirteen (AOR = 0.84; P<0.001), earlier rising again to age 25 (AOR = 1.14; P<0.001). Later this age, at that place was a steady fall equally age increased.

Adapted odds ratios (reference age 40) and total attendances by year of age. Ages above 85 not included due to small totals. Confidence intervals were also small to be displayed. Logistic regression model controlled for age, gender and deprivation. Primary Y axis is a logarithmic scale (base 2). *Adapted odds ratio.

Table three shows the estimated marginal means of daily admissions by weekday and calendar month. Estimated marginal means of daily attendances were highest for both AA and IA in March (39,033 and v,166 respectively) and everyman in August and Dec for AA (34,255 and 34,996 respectively) and in January and December for IA (4,564 and 4,502 respectively). Rate of IA was highest in August and lowest in Dec (12.xx and 11.40 respectively; P<0.001). Mon had the highest estimated marginal means of daily omnipresence for both AA and IA (40,290 and 5,408 respectively) while Fri had the everyman for IA (4,465) and Saturday the everyman for AA (34,475). Rates of IA were highest on Saturday and lowest on Fri (12.31 and 11.17 respectively; P<0.001). Both AA and IA were lowest between midnight and eight am, whilst they were highest between 8 am and 4 pm (Table 4). Rates of IA were highest between 8 am and iv pm, and lowest between midnight and 8 am (12.09 and 8.71 respectively; P<0.001).

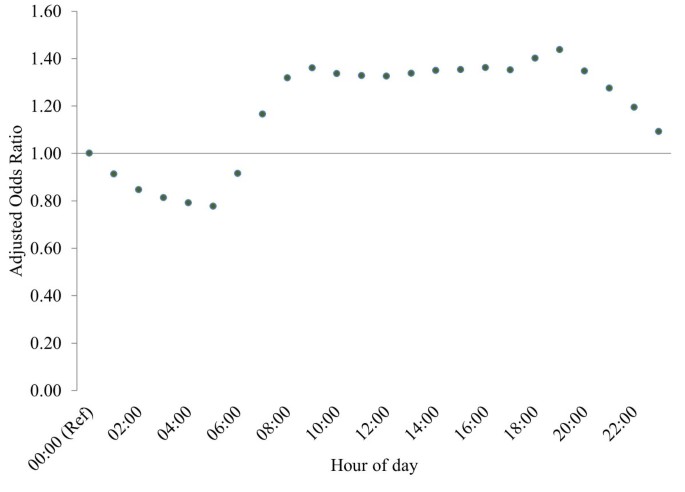

After controlling for various fourth dimension periods of attendance (hour, month, weekday, bank (public) holiday and Christmas period; Tabular array 2), IA had the highest AOR during the months of July and August (both AOR = one.04; P<0.001), on Saturdays (AOR = i.10; P<0.001), and on bank holidays (AOR = ane.13; P<0.001). By contrast, odds of IA were everyman in the months of May and December (both AOR = 0.97; P<0.001), on Fridays (AOR = 0.97; P<0.001), and during the Christmas period (AOR = 0.97; P<0.001) (Tabular array 3). IA were lowest between midnight and 6 am (lowest v am, AOR = 0.78; P<0.001) with attendances increasing after this point to plateau betwixt 9 am and 7 pm (highest 7 pm, AOR = 1.44; P <0.001), then fall once more to midnight (Figure 2).

Adjusted odds ratios for hr of arrival (reference hr is midnight). Confidence intervals were too minor to be displayed. Logistic regression model controlled for hr of arrival, calendar month, weekday, bank holiday and Christmas period.

Discussion

IA are a long-standing concern for EDs and still provide an excess burden on services [13]. This ecological study provides insight into the demographical representation and temporal factors associated with IA to ED. The large sample has immune for a level of analysis that has not been previously performed. Well-nigh 12% of the attendances in our study were accounted inappropriate, a value substantially lower than others reported internationally [4]. This marked difference is probable due to the definition of IA used. Our retrospective definition includes only attendances that were self-referred, received no investigation and either advice or no handling, and were discharged without any follow-upwardly or to primary care. These are hands measurable criteria likely to provide high specificity, just by using a generic definition of IA, it is unavoidable that certain private attendances can be misallocated. For example, attendees who receive simple medication (for example, over-the-counter analgesia) that could readily be provided past other services (like chemist's) will be grouped as appropriate, whereas attendees with sure psychiatric complaints may crave emergency assessment and no other investigation or intervention, and thus exist deemed inappropriate.

Reducing IA to EDs could have a significant effect on the quality and continuity of care provided to patients, and as well on the overall fiscal cost of this service. Using our findings, IA resulted in an estimated cost of nearly £100 million between April 2011 and March 2012, assuming an ED omnipresence with no investigation or significant treatment cost £54 [19]. It should be noted, however, that many costs of EDs are relatively stock-still (such every bit staffing and opening of a department), and further inquiry would be required to examine whether reductions in IA would result in toll saving or increased efficiency and utility of existing resources.

We found age to take a strong human relationship with IA. Odds of IA were highest in the very immature (peak attendances were in ane and two year olds), and elevated between mid-teens and mid-twenties, followed past a steady fall as age increased thereafter. The inverse relationship between IA and age found in our written report has too been identified elsewhere (for example, U.s.a., Canada and Brazil) [twenty–22]. Thus, our findings advise that interventions to foreclose IA should be targeted towards early childhood and immature adults in their late teens to late twenties. For immature children, the determination to nourish ED lies with parents and guardians, and this is likely reflective of the pressures of parenthood and a conventionalities that the ED is the nearly advisable place to receive care [23, 24]. This could be first through targeted teaching to parents about the appropriate use of ED services, or by providing details of other local health services capable of providing prompt medical advice when to access to primary care and out-of-hours services available. This could be delivered routinely via wellness professionals who have a high caste of contact with new parents (for example, through home visits and routine health checks), such equally health visitors, community midwives and nursery nurses.

The second peak in odds of IA seen from late teens to late twenties could reverberate a fourth dimension when young people are leaving dwelling house for the first fourth dimension (such every bit to nourish university), and may indicate a poor understanding regarding appropriate apply of ED services, a lack of knowledge of other health services available, and poor admission to primary care (for example, still registered with childhood general practice). Targeted pedagogy for school leavers and university students regarding advisable employ of ED, alternative wellness services available in the local area and the importance of primary care and registration with a local general practitioner could show useful in reducing IA in this group.

Research in other countries has found that females are more likely to attend ED inappropriately than males (for example, Brazil, Turkey and Usa [22, 25, 26]). Conversely, nosotros found that males were slightly more likely to nourish inappropriately than females, although absolute differences were minor. This may reflect a departure in the definition of IA or differences in the structure and use of health services betwixt countries. Whilst deprivation has been linked to IA in other studies, the direction of association has been mixed and may depend to some extent on the marker of impecuniousness used (for case, education, income, social class or postcode) [thirteen, 25, 27]. Using a measure of residential impecuniousness, we constitute that the nearly deprived population accounted for the highest numbers of both AA and IA. This likely represents the poorer wellness and greater injury risk experienced in deprived communities. Even so, after controlling for age and gender, those from the least deprived quintile had the greatest odds of IA relative to AA. Several mechanisms might explain this finding, including greater admission to ED among more affluent individuals (such as through increased availability of ship) [28], and smaller family size possibly permitting greater focus on private children and increased business organisation over non-urgent weather condition [23, 29]. There is a need for greater clarification effectually this relationship to help sympathise why certain social groups may be more probable to attend inappropriately than others. Although significant, the degree of difference between deprivation quintiles is only pocket-sized and with IA occurring most often in the most deprived communities, measures to manage service pressures by providing additional services and addressing IA would exist of greatest benefit in deprived areas.

Both AA and IA were seen to occur most regularly on Mondays, during March and between 8 am and 4 pm. When controlling for temporal furnishings, relative to AA odds of IA were significantly higher on weekend days, banking concern holidays and between the hours of 8 am and midnight. These findings can inform both the management of ED services and prevention of IA; service provision may exist best targeted on Mondays and betwixt the hours of 8 am and 4 pm, whilst measures to raise sensation may be well-nigh effective if targeted at weekends and Bank Holidays. The increase during weekends and bank holidays likely represents a lack of admission to primary care during these times, and a reluctance to have fourth dimension off work during the calendar week to access these services. Although pregnant, the variation seen in IA by month was smaller than that seen when comparing weekdays to weekends or bank holidays, suggesting that calendar month is unlikely to be a major factor informing service management or prevention measures regarding IA.

Internationally, numerous methods have been used to forestall inappropriate use of EDs. These include diverting calls from emergency services, ambulance non conveyance, attempts to triage out IA and general education [30]. These interventions accept experienced variable success and have raised questions over patient safety [30]. Patient safety is paramount and any potential negative furnishings of intervention (for example, a delay in omnipresence to an ED for an urgent health trouble) must be carefully considered before implementation. A further method of addressing IA, trialed in England, is the provision of primary intendance physicians either alongside emergency physicians in the ED itself, or fastened to the department in a full general practice surgery [11]. This is intended to provide culling options for what is deemed an IA at ED, with research suggesting it is a safe and price-constructive intervention [31, 32], and ane supported by the College of Emergency Medicine [33]. It has been suggested that primary care services are currently bereft to manage the demand for health treatment and require modification to reduce the brunt on ED [16].

The major strength of our study is its telescopic; the HES A&E dataset has provided access to a much larger sample of IA than previously studied and one that represents the bulk of ED attendances in England over a one-yr menstruum. As well, the utilise of the Index of Multiple Impecuniousness has allowed for a more comprehensive review of impecuniousness comparative to previous literature. However, a number of limitations exercise exist. Firstly, alongside potential misallocation of attendances to either the IA or AA groups, only using attendances that were self-referred will accept missed any inappropriate cases referred from primary care, telephone triage services or the ambulance service, while the exclusion of cases who left the ED before being treated or having refused treatment may have further missed IA. Nosotros were too unable to business relationship for variation in staff practices regarding investigation and treatment. Despite this, our definition should human action as a suitable proxy for IA, and results will remain relevant when because prevention or management. Some other limitation is the lack of boosted information which is inevitable when using datasets such as the HES. Data on access to chief care services, reasons for choosing ED equally point of intendance, general impressions of different services and patients' ain view of omnipresence appropriateness will exist of import in determining potential predictors of IA. Additionally, the incompleteness of the dataset is an important limitation. Although small relative to our sample size, over 470,000 attendances were removed because they could non be assigned to an appropriateness category. In add-on, only 62.six% of attendances had a valid diagnosis lawmaking [17], preventing analysis of these information, which would have provided information that could further inform prevention.

This study is the offset to explore IA beyond England as a whole using the HES dataset for ED attendances. Whilst this dataset is currently experimental, coverage beyond England continues to improve each year, with 80.5% of all ED attendances in England included in data for 2011 to 2012 and over 90% of cases having valid data on investigation, treatments and disposal [17]. With an urgent need to reduce the burden on ED across England, this dataset, and the methods detailed in our study, could readily course the basis of a monitoring organization, allowing for timely evaluation of interventions and services implemented to alleviate the ED burden of IA and increase the quality of the service. To strengthen the dataset, an ceremoniousness field could be added, which could convalesce concerns about sensitivity. To practice this, a articulate definition of IA would be required, based on objective criteria rather than subjective evaluation. Such a definition of IA must be highly robust and exclude any omnipresence with a risk of serious sequelae resulting from not-use of ED. A national policy for clinical ED staff to determine appropriateness via these criteria would allow for effective inclusion of IA into the HES A&E dataset.

Conclusions

Our written report adds important evidence to the field of ED omnipresence inquiry. The clear relationship betwixt IA and age indicates that prevention would be best targeted at parents of young children (age nether 10 years) and at young adults (aged 20 to 29). Increased odds of attendance on weekends and depository financial institution holidays, and in younger age groups, suggests that reduced access to primary care is an important cistron in IA. The methods used hither could form the footing of a monitoring system to evaluate the effectiveness of any interventions implemented to reduce IA. These results will be useful in creating policies to either reduce or manage the electric current burden of IA on emergency services.

Abbreviations

- A&E:

-

Accident and emergency

- AA:

-

Appropriate attendances

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- ED:

-

Emergency section

- HES:

-

Infirmary Episode Statistics

- IA:

-

Inappropriate attendances.

References

-

Moskop JC, Sklar DP, Geiderman JM, Schears RM, Bookman KJ: Emergency department crowding, office one—concept, causes, and moral consequences. Ann Emerg Med. 2009, 53: 605-611. ten.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.09.019.

-

Hoot NR, Aronsky D: Systematic review of emergency department crowding: causes, effects, and solutions. Ann Emerg Med. 2008, 52: 126-136. ten.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.03.014. e121

-

Bezzina AJ, Smith PB, Cromwell D, Eagar K: Primary care patients in the emergency department: Who are they? A review of the definition of the 'primary care patient' in the emergency department. Emerg Med Australas. 2005, 17: 472-479. 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2005.00779.10.

-

Carret ML, Fassa Air-conditioning, Domingues MR: Inappropriate employ of emergency services: a systematic review of prevalence and associated factors. Cad Saude Publica. 2009, 25: 7-28. 10.1590/S0102-311X2009000100002.

-

Schull MJ, Kiss A, Szalai J-P: The effect of low-complication patients on emergency department waiting times. Ann Emerg Med. 2007, 49: 257-264. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.06.027. e251

-

Durand A-C, Palazzolo S, Tanti-Hardouin N, Gerbeaux P, Sambuc R, Gentile S: Nonurgent patients in emergency departments: rational or irresponsible consumers? Perceptions of professionals and patients. BMC Research Notes. 2012, 5: 525-10.1186/1756-0500-five-525.

-

Sanders J: A review of health professional attitudes and patient perceptions on 'inappropriate' blow and emergency attendances. The implications for current minor injury service provision in England and Wales. J Adv Nurs. 2000, 31: 1097-1105. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01379.10.

-

Prince M, Worth C: A study of 'inappropriate' attendances to a paediatric accident and emergency department. J Public Health Med. 1992, 14: 177-182.

-

Driscoll PA, Vincent CA, Wilkinson M: The apply of the accident and emergency section. Arch Emerg Med. 1987, four: 77-82. ten.1136/emj.4.ii.77.

-

Ward P, Huddy J, Hargreaves S, Touquet R, Hurley J, Fothergill J: Primary care in London: an evaluation of general practitioners working in an inner city accident and emergency department. J Accid Emerg Med. 1996, 13: 11-15. 10.1136/emj.13.1.11.

-

Carson D, Clay H, Stern R: Primary Care and Emergency Departments. 2010, Lewes, East Sussex: Primary Intendance Foundation

-

Martin A, Martin C, Martin Pb, Martin PA, Green One thousand, Eldridge Southward: 'Inappropriate' attendance at an accident and emergency department by adults registered in local full general practices: how is it related to their utilize of chief care?. J Wellness Serv Res Policy. 2002, vii: 160-165. 10.1258/135581902760082463.

-

Harris MJ, Patel B, Bowen Due south: Principal care admission and its human relationship with emergency department utilisation: an observational, cross-sectional, ecological study. Br J Gen Pract. 2011, 61: e787-e793. 10.3399/bjgp11X613124.

-

Blow and emergency survey. 2012, http://www.cqc.org.britain/public/reports-surveys-and-reviews/surveys/accident-and-emergency-2012.

-

NHS foundation trusts: review of nine months to 31. 2012, http://www.monitor-nhsft.gov.uk/node/2302, December .

-

Health Committee - 2d report: urgent and emergency services. http://world wide web.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201314/cmselect/cmhealth/171/17103.htm.

-

Health and Social Care Information Heart: Hospital Episode Statistics: Accident and Emergency Attendances in England (Experimental Statistics) 2011–12. Summary Report. 2013, Leeds: Health and Social Care Information Centre

-

Department for Communities and Local Government: The English Indices of Deprivation 2010. 2011, London: Section for Communities and Local Government

-

Payment by results in the NHS: tariff for. 2012, https://www.gov.united kingdom of great britain and northern ireland/government/publications/confirmation-of-payment-by-results-pbr-arrangements-for-2012-thirteen, to 2013.

-

Davis JW, Fujimoto RY, Chan H, Juarez DT: Identifying characteristics of patients with low urgency emergency department visits in a managed intendance setting. Manag Intendance. 2010, 19: 38-44.

-

Afilalo J, Marinovich A, Afilalo Yard, Colacone A, Léger R, Unger B, Giguère C: Nonurgent emergency department patient characteristics and barriers to primary intendance. Acad Emerg Med. 2004, 11: 1302-1310. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2004.tb01918.x.

-

Carret Grand, Fassa A, Kawachi I: Demand for emergency health service: factors associated with inappropriate use. BMC Wellness Serv Res. 2007, seven: 131-ten.1186/1472-6963-seven-131.

-

Hendry SJ, Beattie TF, Heaney D: Minor affliction and injury: factors influencing attendance at a paediatric accident and emergency section. Arch Dis Child. 2005, 90: 629-633. 10.1136/adc.2004.049502.

-

Kai J: What worries parents when their preschool children are acutely ill, and why: a qualitative report. BMJ. 1996, 313: 983-986. 10.1136/bmj.313.7063.983.

-

Oktay C, Cete Y, Eray O, Pekdemir K, Gunerli A: Appropriateness of emergency department visits in a Turkish university hospital. Croat Med J. 2003, 44: 585-591.

-

Liu T, Sayre MR, Carleton SC: Emergency medical care: types, trends, and factors related to nonurgent visits. Acad Emerg Med. 1999, six: 1147-1152. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00118.x.

-

Pereira S, due east Silva AO, Quintas Thousand, Almeida J, Marujo C, Pizarro M, Angélico V, Fonseca L, Loureiro E, Barroso S, Machado A, Soares Thousand, da Costa AB, de Freitas AF: Appropriateness of emergency department visits in a Portuguese university hospital. Ann Emerg Med. 2001, 37: 580-586. 10.1067/mem.2001.114306.

-

Rudge GM, Mohammed MA, Fillingham SC, Girling A, Sidhu K, Stevens AJ: The combined influence of distance and neighbourhood deprivation on emergency department attendance in a large English population: a retrospective database study. PLoS One. 2013, 8: e67943-10.1371/journal.pone.0067943.

-

Bradshaw J, Finch N, Mayhew East, Ritakallio V-G, Skinner C: Kid poverty in Large Families. 2006, Bristol: Joseph Rowntree Foundation

-

Cooke M, Fisher J, Dale J, McLeod E, Szczepura A, Walley P, Wilson S: Reducing Attendances and Waits in Emergency Departments: a Systematic Review of Nowadays Innovations. 2005, Warwick: National Found for Health Research

-

van der Straten LM, van Stel HF, Spee FJM, Vreeburg ME, Schrijvers AJP, Sturms LM: Safety and efficiency of triaging low urgent self-referred patients to a general practitioner at an acute care post: an observational study. Emerg Med J. 2012, 29: 877-881. 10.1136/emermed-2011-200539.

-

Bosmans JE, Boeke AJ, van Randwijck-Jacobze ME, Grol SM, Kramer MH, van der Horst HE, van Tulder MW: Add-on of a general practitioner to the accident and emergency department: a cost-effective innovation in emergency intendance. Emerg Med J. 2012, 29: 192-196. 10.1136/emj.2010.101949.

-

The College of Emergency Medicine: The College of Emergency Medicine Welcomes New Written report into the Human relationship Betwixt Primary Intendance and EDs. 2010, London: The College of Emergency Medicine

Pre-publication history

-

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed hither:http://world wide web.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/eleven/258/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and thank Michela Morleo for assisting with ethics application and project planning, Nicola Leckenby for performing quality balls and Dr Jane Mcvicar for advice regarding the manuscript editing.

Author information

Affiliations

Respective author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MAB and PM designed the study. PM analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. SW co-drafted the manuscript and contributed to data analysis. MAB and KH contributed to data analysis and manuscript editing. UD contributed to manuscript editing. SWy extracted the data. All authors read and canonical the concluding manuscript.

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

This article is published nether license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access commodity distributed under the terms of the Artistic Eatables Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/ii.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in whatever medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/cipher/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this commodity, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Nigh this article

Cite this commodity

McHale, P., Wood, Southward., Hughes, K. et al. Who uses emergency departments inappropriately and when - a national cross-sectional report using a monitoring data system. BMC Med 11, 258 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-258

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-258

Keywords

- Emergency department

- Inappropriate attendance

- Wellness service use

What About Someone Who Uses Emergency Services Twice A Month,

Source: https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1741-7015-11-258

Posted by: billshingst.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What About Someone Who Uses Emergency Services Twice A Month"

Post a Comment